The Revolutionary Vision of Otto Neurath

When Austrian philosopher Otto Neurath died in Oxford some 80 years ago, far from his native Vienna, he was still finding his feet in exile. Like many Jewish refugees, the economist, philosopher and sociologist had been interned as a suspected enemy alien on the Isle of Man, along with his third wife and close collaborator Marie Reidemeister, after a last-minute escape from their interim hideout in the Netherlands across the Channel in a rickety boat in 1940.

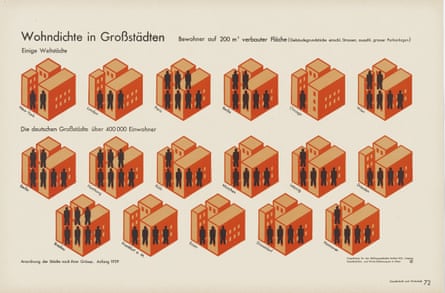

Thanks to Neurath's pioneering use of pictorial statistics – or "Isotypes" as Reidemeister called them (an acronym for "International System of Typographic Picture Education") – he left behind an enormous legacy in the arts and social sciences. This became the language through which we decode and analyse the modern world, though his lasting relevance would have been hard to predict at the time of his death at age 63.

Photograph: Otto and Marie Neurath Isotype Collection, University of Reading

From Socialist Ideals to Pop Culture

At that point, his Vienna Method of Pictorial Statistics had relatively little impact in the UK beyond providing simplified imagery to leftist film-maker Paul Rotha's public information shorts. Neurath's "visual autobiography" had been shelved by publishers who probably failed to follow the ambitious arc of its title, "From Hieroglyphics to Isotype."

This unpublished tome – which remained so until 2010 – outlined his democratising vision for overcoming educational class divides, crystallised in the powerful slogan: "Words divide, pictures unite."

This harked back to the socialist spirit of interwar 'Red Vienna', seemingly at odds with capitalist postwar Anglo-American pop culture. Yet Neurath's enthusiasm for modern reproduction methods corresponded perfectly with pop as mass-manufactured art without a unique original. Just as advertising slogans or pop songs aim for instant appeal, Neurath demanded images that "show the most important thing about the object at first glance."

The Artistic Legacy and Modern Applications

In retrospect, his thoughtful semiotics anticipated much of pop art. While pop music follows hedonistic principles, Neurath's aims went far beyond utilitarian. As a key figure in Vienna's social housing programme, he placed "happiness" above practical advantages of typification, stating that "the optimal technical solution by no means always coincides with the greatest happiness."

Neurath was also enamoured with new technology, championing fellow exile Wolja Saraga's Saraga-Generator – an early electronic instrument akin to the theremin – and predicting creation of an artificial "Isotype voice" for future documentary films.

This technological foresight explains why in 2017, UK synthpop duo Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark – who used synthesised speech as far back as 1983's Dazzle Ships – released a track called Isotype. The song celebrated Neurath's "fucking genius," according to singer Andy McCluskey.

Photograph: Alicia Canter/The Guardian

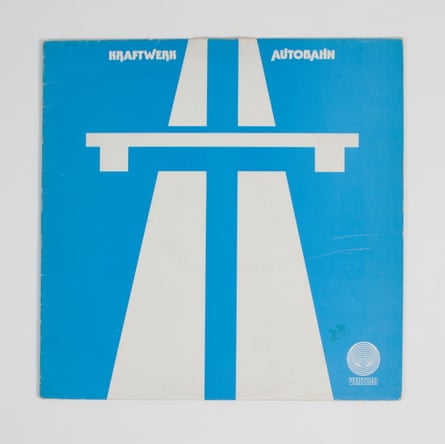

Both McCluskey and graphic designer Peter Saville – who fashioned OMD's early album aesthetics and Factory Records' corporate identity – discovered Neurath's method in the early 1980s. To them, the de-ornamentalised style of Isotype – mostly designed by Neurath's artist Gerd Arntz – perfectly pre-empted the graphic asceticism of the post-punk era.

"We liked the idea of reducing things to the minimum and still getting the point across," says McCluskey. "We had both grown up with Kraftwerk's Autobahn album, which in its later guise was the simple Isotype of the autobahn sign with the two highways and the bridge on a blue background."

Contemporary Relevance and Critical Perspectives

However, McCluskey expresses ambivalence about Neurath's proto-pop imagery. "What kind of worried me was one of Otto Neurath's phrases: 'To remember simple pictures is better than to forget accurate figures,'" he says. "Originally that would have been a mantra I adored. But it's also a scary predictor of the world we live in now, in terms of soundbites and our limited capacity to understand. Doesn't it sound like Donald Trump's whole political mantra?"

The video for OMD's Neurath tribute is a moving mandala of isotypes by German artist Henning M Lederer, featured prominently in "Wissen für alle: Isotype" ("Knowledge for all"), a new exhibition on Neurath's work and legacy at Wien Museum in Vienna.

Featuring original posters designed for Neurath's mass-reproducible "museums of the future," this compact but effective display brims with the socialist utopian energy that coursed through Vienna before Austro-fascism and the Nazi regime. What might have seemed like nostalgia years ago now feels like a rediscovered manual for resistance – a useful reminder of how leftwing politics tackled intellectual snobbery to make itself understood.

Comments

Join Our Community

Sign up to share your thoughts, engage with others, and become part of our growing community.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts and start the conversation!