Rediscovering a Forgotten Design Pioneer

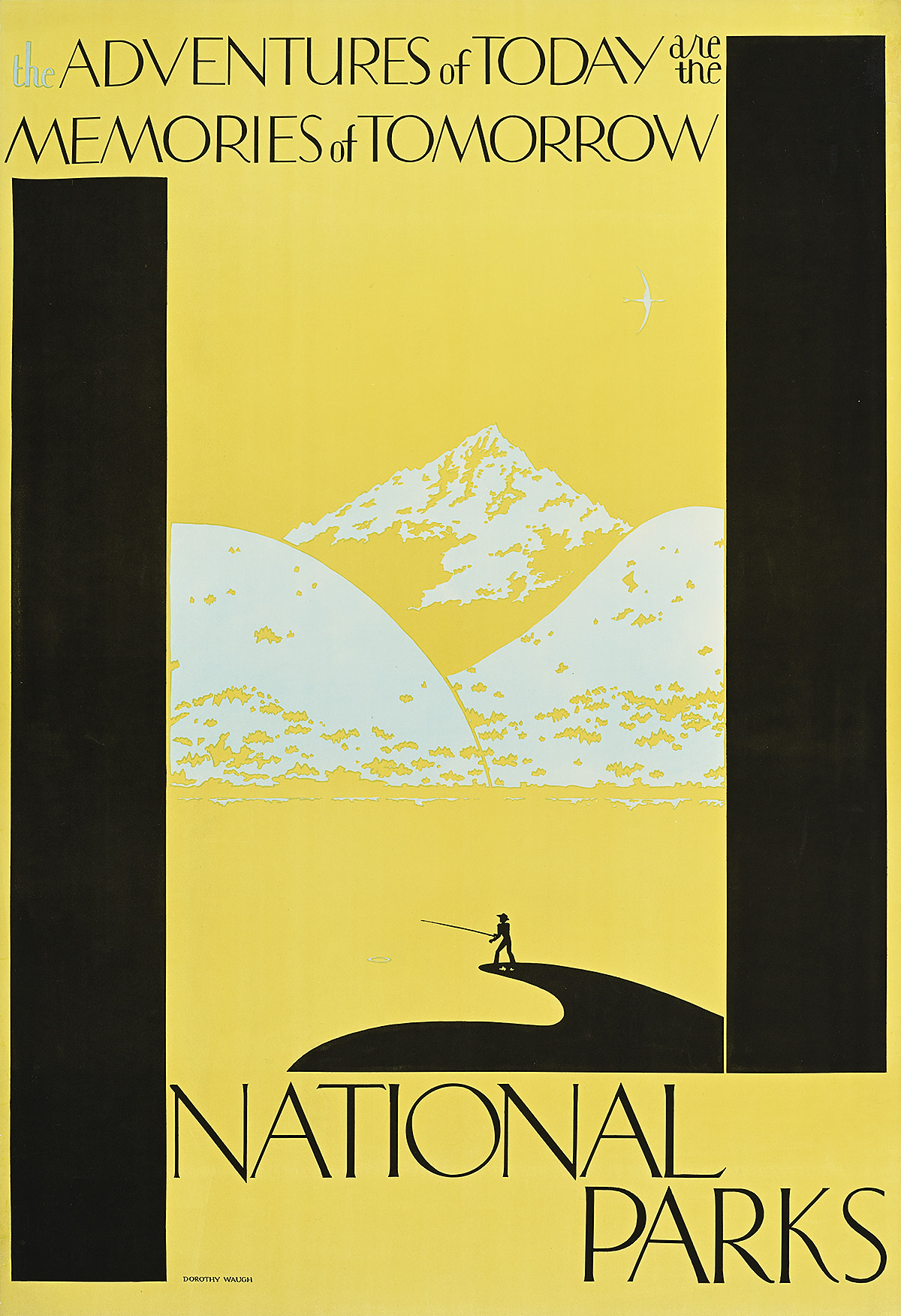

Dorothy Waugh, a pioneering Modernist designer who created the U.S. government's first in-house National Parks poster campaign during the Great Depression, is finally getting her due with her first-ever solo exhibition—a show 30 years in the making.

At New York's Poster House, "Blazing a Trail: Dorothy Waugh's National Parks Posters" reunites all 17 posters Waugh designed for the National Park Service between 1934 and 1936. These bold, experimental works helped define a new visual language for federal design while breaking ground for women in a male-dominated field.

"The federal government had never sponsored their own in-house poster campaigns, full stop—let alone had a solo female Modernist designer do such a campaign in what was a very male-dominated bureaucracy," said arts consultant and guest curator Mark Resnick.

Dorothy Waugh, ca. 1930. Courtesy of the Jones Library, Inc., Amherst, Massachusetts, via Poster House.

Dorothy Waugh, ca. 1930. Courtesy of the Jones Library, Inc., Amherst, Massachusetts, via Poster House.

The 30-Year Quest to Uncover Her Story

Resnick first spotted Waugh's work in the 1990s and was struck by its strong Modernist design that bucked conventions. Shocked to find almost no information about the artist, he embarked on a three-decade journey to uncover her story.

Through extensive research across the National Archives, Library of Congress, Art Institute of Chicago, National Park Service, and the Jones Library in Amherst, Resnick pieced together Waugh's remarkable career.

"The lure of the national parks" by Dorothy Waugh, 1937. Photo: Pierce Archive LLC/ Buyenlarge via Getty Images.

"The lure of the national parks" by Dorothy Waugh, 1937. Photo: Pierce Archive LLC/ Buyenlarge via Getty Images.

Redefining Government Design During the Great Depression

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt believed National Parks were national treasures that could bolster Americans' shattered morale during the Great Depression. As Roosevelt declared 1934 National Parks Year, Waugh pushed to mount a poster campaign for the occasion—and the poster subsequently became a crucial tool of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the U.S. government.

Waugh's lithographs represented a new strategy for the NPS, which had previously let railroads handle all advertising. Instead of straightforward depictions of scenic landscapes, Waugh chose images that spoke broadly to what National Parks offered—wildlife, winter sports, and outdoor activities.

Dorothy Waugh, National Parks/Winter Sports (1935). Private collection. Courtesy of Poster House.

Dorothy Waugh, National Parks/Winter Sports (1935). Private collection. Courtesy of Poster House.

A Distinctly Modernist Approach

Waugh's work was distinctly optimistic, using bold color palettes, graphic shapes bordering on abstraction, and hand-drawn lettering with unique letterforms. Her approach was informed by European Modernism but incorporated American iconography in the realm of commercial illustration.

The Challenge of Preserving Ephemeral Art

Though the NPS printed thousands of each poster, Waugh's designs were essentially ephemera, and many haven't survived. Tracking down all 17 posters—mostly from a single anonymous collector—was a major challenge. One design almost eluded Resnick until a friend recognized it from her Upstate New York country house.

According to the Artnet Price Database, 35 of Waugh's posters have come to auction in the last 25 years, with her "Winter Sports" design selling for a record $2,922 at Christie's in 2008.

Dorothy Waugh, National and State Parks (1936). Collection of Cathy M. Kaplan. Courtesy of Poster House.

Dorothy Waugh, National and State Parks (1936). Collection of Cathy M. Kaplan. Courtesy of Poster House.

A Renaissance Woman of Many Talents

Waugh was "quite the Renaissance woman," Resnick said. After studying at the Art Institute for 10 years, she worked for the NPS as a landscape architect, following her father Frank Waugh into the field. She was hired as part of the New Deal's Civilian Conservation Corps, helping design new visitor facilities for parks.

After leaving the NPS, Waugh founded and led Knopf's Books for Young Adults Division, worked for 25 years as head of public relations at the Montclair Public Library, and offered the first-ever typography course at what's now Parsons School of Design.

She also moonlighted as a journalist, poet, radio personality, children's book author and illustrator, and published two scholarly books on Emily Dickinson—the last when she was 94 years old.

Dorothy Waugh, National Parks/Where the Deer and the Antelope Play (1934). Private collection. Courtesy of Poster House.

Dorothy Waugh, National Parks/Where the Deer and the Antelope Play (1934). Private collection. Courtesy of Poster House.

Why Her Legacy Was Nearly Lost

Resnick believes Waugh's longevity and versatility worked against her. She was largely forgotten by her death in 1996, single with no children or surviving family to safeguard her legacy.

"She did her most public work early in her career. She was a commercial artist as much as anything else," Resnick explained. "Had she elected to just pursue a fine art or graphic design practice deeply for a whole career, she might well be a household name. But she wouldn't have been her."

Instead, Waugh returned again and again to a seemingly bottomless well of creativity throughout her 99-year lifespan, working across mediums and fields. She never returned to poster design after leaving the NPS—but that body of work now provides the perfect entry point for revisiting her impressive career.

"Blazing a Trail: Dorothy Waugh's National Parks Posters" is on view at Poster House, 119 West 23rd Street, New York, New York, September 27, 2025–February 22, 2026.

Comments

Join Our Community

Sign up to share your thoughts, engage with others, and become part of our growing community.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts and start the conversation!